Global Temperatures and the Energy Gap

The summer of 2022 will be etched in the memories of many, marking the first time in the UK’s history when temperatures reached 40°C (the UK’s longstanding temperature record makes this event quite remarkable). These conditions were not confined only to our shores; temperatures across multiple continents exceeded the norm, and NASA satellite observations revealed that Arctic and Antarctic sea ice coverage had melted to record (or near-record) lows.

In comparison, the summer of 2023 was relatively mild. The hottest day, during the September heatwave, saw the Met Office recording a high of 33.5°C in Kent[1]. Nevertheless, this warmth was mostly confined to southern England and Wales, making September unseasonably warm for those areas.

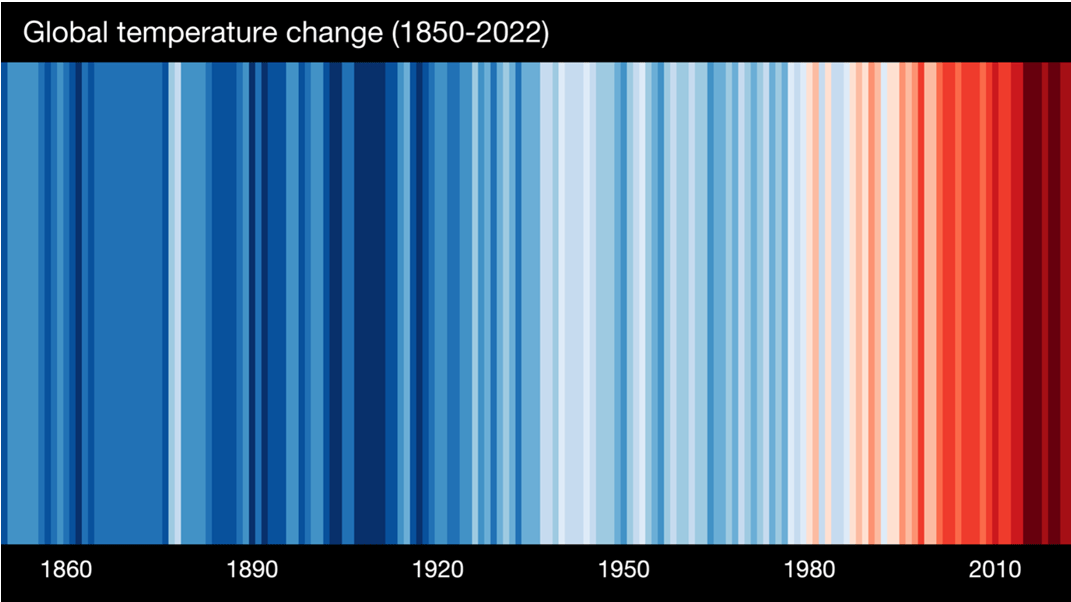

Globally, though, the average temperature was so high last year that Professor Ed Hawkins, a climate scientist at the University of Reading, had to add a deeper shade of red to his climate stripes graphic[2], which represents the average temperature each year since 1850 compared to the long-term average. The right end of the image, dominated by red bars, illustrates the potential influence of human-induced climate change.

With the high figure of 2023 being lower than that of 2022, how could this be? This is explained by the fact that, on average, temperatures surpassed the norm in eight out of 12 months in 2023[3]. Additionally, 2023 marked the first year on record that every single day surpassed pre-industrial levels by more than 1°C. Nearly half of these days exceeded 1.5°C, with some approaching 2°C[4]. These numbers may sound small, but they signify a substantial increase in accumulated heat, carrying profound implications for global ecosystems and weather patterns.

The data underscores the necessity for governments to set more ambitious climate goals. While we recognise the collective responsibility of all parts of society – governments, companies and individuals – in these efforts, it is crucial to acknowledge the role that governments play in shaping governance, policymaking and systemic change.

Governments are particularly influential in steering the transition to renewable energy. Their power to implement policies incentivising the development and deployment of renewable technologies not only benefits the environment (by reducing greenhouse gas emissions), but also enhances national energy security, ultimately reducing energy bills for households and businesses. In the UK, about 40% of electricity generation comes from renewable sources[5] (via about 1,000 solar farms[6], 1,500 operational onshore and offshore wind farms[7], and 1,500 hydropower plants[8]). A further 14% comes from nuclear power. However, the current renewable generation of 175 terawatt-hours falls short of the domestic consumption of 275 terawatt-hours a year, necessitating a scaling up of renewable farms and plants to bridge this gap.

Regardless, a 2023 study by campaign group Britain Remain[9] reveals that over 70 councils across England collectively opposed one-fifth of renewable project applications, capable of powering an estimated 4.4 million homes for a year. One significant reason for rejection is the impact on agriculture: solar/wind farms are often criticised as land-intensive, raising concerns about competition for finite land resources that could otherwise be used for food production. In a world already grappling with issues such as soil degradation and water shortages affecting agricultural productivity, energy goals must be carefully balanced with the need for sustainable food production. Another aspect contributing to opposition is the impact on the landscape, with some arguing that such farms and plants are eyesores that mar the natural beauty of the countryside.

Encouragingly, technological advancements offer promising solutions to address these concerns. Notable strides have been made in developing solar panels with improved performance and efficiency, reducing the land footprint of solar farms while maintaining substantial energy outputs. Innovation such as bifacial solar panels (capable of capturing sunlight from both sides) contribute to increased energy yields without a proportional increase in the land footprint. Similar progress in wind energy technology has led to the creation of turbines with blades made from innovative materials, enhancing efficiency and durability.

This progress in renewable energy, coupled with the growing demand for sustainable solutions, creates an attractive landscape for investment. Our SRI portfolios reflect our commitment to fostering environmentally conscious opportunities, with funds such as Ninety One Global Environment (which invests primarily in companies that are contributing to sustainable decarbonisation) and M&G Global Sustain Paris Aligned (which invests in companies that contribute to climate change goals) aligning with our values of promoting sustainability.

Sources:

- [1] Microsoft Word – Seasonal Assessment – Autumn23.docx (metoffice.gov.uk)

- [2] Ed Hawkins on X: “2023 was the warmest year on record globally by a large margin. Another dark red stripe gets added, though I think I need a new colour. #ShowYourStripes https://t.co/un1pNGmNmw” / X (twitter.com)

- [3] 2023 was second warmest year on record for UK – Met Office

- [4] Copernicus: 2023 is the hottest year on record, with global temperatures close to the 1.5°C limit | Copernicus

- [5] Electricity production in the United Kingdom (ourworldindata.org)

- [6] Solar Farms – Large Scale Solar Panel Farms For Business (eonenergy.com)

- [7] Onshore vs offshore wind energy: what’s the difference? | National Grid Group

- [8] UK: hydro energy sites 2022 | Statista

- [9] Councils oppose clean energy projects despite declaring climate emergency – Energy Live News